The examination of Egyptian pyramids caused massive speculation in the

19th century. Reflecting the religious beliefs of the Egyptians, with their

concept of the afterlife, mixed in with astrology and the shape of the sun’s

rays, the structures soon inspired theories as to their construction and

purpose. In particular this applied to the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The founding father of what came to be commonly known as pyramidology was John Taylor who

published The Great Pyramid: Why was it Built? And Who Built it? in 1859. He

greatly influenced Charles Piazzi Smyth, Astronomer Royal of Scotland, who

followed with Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid in 1864. Smyth visited Egypt

– something Taylor never did – and as a respected astronomer gained considerable

attention. Moved by his beliefs, when he died in 1900, his monument in the

graveyard of St. John’s Church, Sharow, near Ripon, was a pyramid.

Smyth’s pyramid – photo credit Julia & Keld

After Smyth’s book, the baton was taken up

by an American Lutheran minister, Joseph Augustus Seiss, in 1877, with the

publication of The Great Pyramid of Egypt, Miracle in Stone. As a result, in the

last few decades of the 19th century many religious groups believed that the

Giza pyramid was not a tomb, but had been constructed to reveal God’s plan for

mankind to future generations. The measurements of certain features would equate

to time periods, and would tie in with scripture.

The concept was widely

accepted, although the interpretations of the “evidence” varied from writer to

writer. It also changed as different surveyors re-measured the edifice and came

up with revised figures from those accepted by Seiss and early writers. Today it

is often associated with Anglo-Israelites, those who believe that the ten lost

tribes of Israel can be traced down to the British nation.

Charles Taze Russell

would be one of many who mentioned the pyramid. In his 1916 forward to Volume 3

of Studies, he wrote: “We have never attempted to place the Great Pyramid,

sometimes called the Bible in Stone, on a parallel or equality with the Word of

God as represented by the Old and New Testament Scriptures – the latter stand

pre-eminent always as the authority.”

However, he did view the Great Pyramid to

be a corroborative witness.

Certain other Bible Students focused on the pyramid

far more extensively. William Wright corresponded with Piazzi Smyth (the

correspondence is in Studies volume 3) and two brothers, John and Morton Edgar

of Glasgow, wrote several books on the subject, including Great Pyramid Passages

volumes 1 and 2.

When the Watch Tower Society arranged for its own burial plot

at United Cemeteries, Ross Township, a central memorial for the plot was

designed by John Adam Bohnet in the shape of a pyramid. However, this was not a

special sign or even a grave marker for any individual, but rather a communal

monument designed to record the names of those buried on site in four quadrants

around it, linked to the four pyramid sides. As it happened, only nine names

were ever recorded before the idea was abandoned. The structure was eventually

removed for safety reasons.

Pyramid (L) and CTR’s grave marker (R) c. 1921

As

time passed, general interest in pyramid theories waned in the mainstream.

Finally, in 1928, after little comment for several years, the Watch Tower magazine

produced two articles on the subject in the November 15 and December 1, 1928,

issues. The gist of their arguments, which were against the Giza pyramid being

of God, were reproduced in more recent times, in The Watchtower for May 15,

1956.

The correspondence columns of the Watch Tower had various responses after

the 1928 articles, best summed up by a future president of the Watch Tower

Society (issue of July 1, 1929):

The Golden Age magazine (January 23, 1929) had

some fun naming certain individuals who no longer associated with the I.B.S.A.

and who had made new predictions based on the pyramid. One was Morton Edgar.

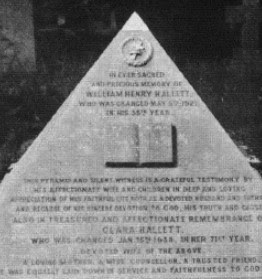

Of

course, those who did not agree with the Watch Tower’s new position continued to

believe in pyramidology, and in at least one case, tried to emulate Smyth. From

a Yeovil (Somerset, UK) cemetery is this example.

The last inscription on its

sides was for Clara Hallett, who died in 1938.

Her husband, Bible Student

William Henry Hallett, had died in 1921.

Perhaps surprisingly, the family who

had done so much to promote the concept, the Edgars, did not go for a pyramid

monument themselves. Most of the Edgars, including writers John and Morton, are

buried in a family plot in the Eastwood (Old) Cemetery, Glasgow, and chose to

have no monuments or headstones at all.

With thanks to the Glasgow and West of

Scotland Family History Society volunteer who checked the printed records and

then took the photograph. There are sixteen Edgar graves (four plots, four deep)

on either side of the tree in the middle of the picture. One wonders what size

the tree was when the plots were sold originally.

Perhaps to end on a really

bizarre note: London could today have had the largest pyramid on earth if the

plans of architect Thomas Willson (1781-1866) had been realised. Detailed plans

were drawn up and investors invited for what would be called The Metropolitan

Sepulchre.

It was designed to work a bit like a modern multi-storey car park and

was to be built on top of Primrose Hill. Had it been approved it would have been

four times the height of St Paul’s Cathedral, and would hold an estimated five

million dead Londoners.

What a landmark that would have become, towering far

higher than the Great Pyramid of Giza if put side by side. The plans were first

put before parliament in 1830, and later at the Crystal Palace Great Exhibition

of 1851 for another proposed location. But ultimately garden cemeteries (out of

town with help from new-fangled railways) and later crematoria were more

practical solutions.

Can you imagine the problems Willson’s pyramid would have

caused for future generations when it was full? And what a useful landmark it

could have been for German bombers in World War 2.