The history of the 19th century Bible Student movement, with occasional more recent developments among those who stayed with the Watch Tower Society. A place for historians who love this subject. Not a place for polemics or for debating beliefs; simply history written as neutrally as possible. Enjoy! Some reprinted pieces first appeared on: truthhistory.blogspot.com

Saturday, 21 December 2019

Monday, 16 December 2019

Tuesday, 3 December 2019

Bible House family - 1906

The date 1906 is written on the back of one

collector’s copy of this photograph. However, another copy came to me with the date August 1907

attached to it, but with no documentary evidence. Yet another copy surfaced

which just said pre-1909, which obviously has to be true because that is when they

moved to Brooklyn. Also Estella Whitehouse married Isaac Hoskins (both in the

picture) in January 1908. If any readers have positive documentary proof for

the date it would nice to know.

Most will recognise a few of the people. Bohnet, Van

Amburgh and Hirsh leap off the page for me. CTR is not there (a fanciful

thought, maybe he was behind the camera) and neither is his sister Margaret,

although Margaret’s daughter, Alice Land, is there.

I had a little difficulty working out rows one and

two until I carefully checked the feet in the photograph. The rows are counted

from the front to the back.

Addenda: I have it on very good authority from someone who has checked all the directories year by year for Allegheny that this group of people were there in 1907. A future article will cover the personnel in Bible House year by year. When that article is eventually published it will replace this one, which will be taken down at that point.

Addenda: I have it on very good authority from someone who has checked all the directories year by year for Allegheny that this group of people were there in 1907. A future article will cover the personnel in Bible House year by year. When that article is eventually published it will replace this one, which will be taken down at that point.

Friday, 29 November 2019

Some you win... Some you - don't...

This is a brief tale of a search that in some ways

led to disappointment. Being based in the UK I was asked if I could find the

last resting place of the Edgar family. As well as their speciality of pyramidology

three of the Edgars, John, Morton and Minna (two brothers and a sister) also

wrote a series of little booklets. One of them by John “Where are the dead” was

instrumental in attracting the interest of a young man named Fred Franz before

the First World War.

We knew from printed accounts that they were buried

in a family plot in the Eastwood Cemetery, Glasgow. There are two cemeteries of

this name, an Old and a New, but the date of the first interment identified the

site as being in the Old.

Were there memorial headstones? Would there even be

a pyramid? That is not as fanciful as it sounds. Here is the grave for Piazzi

Smyth.

And here from a Bible Student publication is a grave

marker in Yeovil, Somerset, for a Bible Student, William Hallett, who died in

1921.

The cemetery records in Glasgow had not been

transcribed, let alone posted on the internet. But I was able to make contact

with a Family History Society in Glasgow and a member very kindly did a search

for me. Almost immediately the burial registers for the family were found.

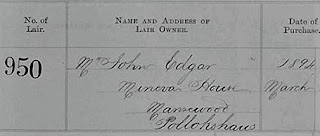

John bought three adjoining plots and later a fourth

was added, totalling plots numbered A-950-953. Sixteen members of the extended

family were eventually buried here. The last interment was in 1968. Any modern

generations of the family, if they still exist, obviously moved elsewhere.

The next step was a visit to the area and again a

willing volunteer from the area visited the site and took the following

photograph. The graves numbered A-950-953 are both sides of the tree in the

foreground. One wonders what size the tree was when these plots were sold

originally.

There are a few memorials standing, which at least enable

one to fix the correct site, but alas, none for the Edgar family. In UK

cemeteries vandalism and sheep with itchy bottoms have eliminated a lot of memorials,

but it would appear from the photographs that the Edgars never did have a

lasting memorial installed.

Realistically, had there been anything like a

pyramid there, it would have been found and publicised long before now.

So this is a non-story really. But you never know

until you follow everything up what may or may not be discovered.

Wednesday, 27 November 2019

Photodrama films

Those who love the Photodrama of Creation will

recognize these frames from the end of the sequence on the flood, with the

tinted sequence of the ark that ends with the rainbow appearing.

After the footage was meticulously copied frame by

frame, the key nitrate stock in private hands was donated to the George Eastman

museum as they have the professional facilities for its preservation.

Also the following document has come to light from

the time which details the order and contents of all the slides and moving

pictures from the production.

Interestingly it is dated November 17, 1914, and

stresses that this revised schedule should be followed “implicitly.” Although

the Photodrama started life as a three parter for a very short time, it had been

shown in four parts for most of 1914. The extra part was not so much adding

extra material as making each performance of a more manageable length for audiences

of the day. But one wonders what changes were deemed necessary by November of

that year.

Monday, 18 November 2019

Handling the Tetragrammaton in English translations

William Tyndale’s translation from Exodus 6 as first

published in 1530.

This blog has already

republished two articles from the journals of The International Society of

Bible Collectors, one on Herman Heinfetter and one on Age to Come Bibles. This

third article, which dates from 1988, was published originally in Bible

Collectors’ World. It has not been updated since its original publication.

The article was specific

to translations of the commonly called Old Testament. It has no direct

connection with the Bible Student movement (although ZWT used the name Jehovah

over two thousand two hundred times, starting with the supplement to the very

first issue of July 1879 through to the end of 1916). And the modern Watchtower

Society has produced the New World Translation, which extensively uses the form

Jehovah. As such, the subject matter may be of interest to some blog readers.

Footnote numbers are

printed in red.

A past issue of The Bible Collector (No. 57) contained an article on

“The Divine Name in Bible Translation.” This described some Bible versions of

the past 150 years that restored the Divine Name in the text in some readable

form, generally as Jehovah or Yahweh. The purpose of this article is to

illustrate how this translation problem has been handled in at least a dozen

different ways in English language versions of the Old Testament (OT).

The background only need be covered briefly here. The special name for

God in the Hebrew text is written as four letters (Greek: tetragrammaton,

hereinafter abbreviated at TG). These letters are usually transliterated as

YHWH. By about 700 AD Jewish “masters of tradition” (Massoretes) were adding a

system of vowel points to indicate the accepted pronunciation. When handling

the TG, vowel points for Adonai (Lord) and Elohim (God) were deliberately

inserted. This reminded the reader that “Lord” or “God” should be substituted

in public reading. It had long been Jewish practice not to pronounce the sacred

name. When translations were made into Greek, and later Latin, it became

accepted practice to substitute words such as “Lord” in the translation. The

first English versions from the Latin simply passed on this earlier decision.

This background has resulted in two opposing viewpoints amongst

translators today. One is to follow the long established practice of

substituting a title for the TG, usually LORD in all capitals. Smith and Goodspeed’s

American Translation calls this following “the orthodox Jewish tradition.” 1 However, there are certain texts such as Exodus 6:3 where many feel the

sense is incomplete without a proper name. On such occasions many leave

tradition and insert a form of the TG. This pattern, started with Tyndale, was

popularized by the KJV which used the form Jehovah on four occasions. 2

The alternative view is that the name should be consistently restored in

the English version, wherever this can be supported by the Hebrew text.

Depending on the actual text used this can vary between 5,500 3 and nearly 7,000 4 times. It is held

that later Jewish tradition should not be the determining factor. If the

earliest extant manuscripts (including the Dead Sea Scrolls) use a distinctive

name so many times, then accurate translation demands the same. But what form

should the name take?

There are of course many translations that do not fit comfortably into

either above category. Some appear very inconsistent, using names or titles on

the apparent whim of the translator (cf. Living Bible). The New Berkeley

Version (1969) even manages to contain both Jehovah (Exodus 6:3) and Yahweh

(Hosea 12:5) within the same translation!

An attempt will now be made to describe some different ways the TG has

been handled in the history of OT translation. The following survey does not

claim to be exhaustive. The dates in brackets relate to OT publication, which

in many cases will mean the complete Bible. An asterisk (*) following the date indicates

that the volume is featured in Herbert. 5

LORD/GOD

The reasons for substituting the title LORD have been outlined above.

Versions consistent in this practice include Revised Standard Version (1952*),

New American Bible (1970), New American Standard Version (1971), Good News

Bible (1976) and New International Version (1978). These are amongst the most

popular versions in use. The general reading public for whom they are addressed

can easily remain unaware of the TG, unless they check a forward or footnote.

Even in Exodus 6:3 the form LORD is retained.

It is interesting to note that the supervising translator of the Good

News Bible, Robert Bratcher, has recently commented: “A faithful application of

dynamic equivalence principles would require a proper name, and not a title, as

a translation of YHWH…In the matter of the names for God, the GNB is still far

from being a ‘perfect’ translation.” 6 It can also be noted that the NIV text used in Kohlenberger’s Hebrew

Interlinear (1979-86) has restored the form Yahweh.

Other popular versions of the 20th century that generally use LORD, but

make an exception in Exodus 6:3 include New English Bible (1961*). American

Translation (OT 1927*), and Basic English (1949*). The usual practice is to

print LORD in capitals when it substitutes for the TG. (This is not always the

case. The much reprinted Douay-Challoner version uses small case letters,

creating a problem of identity in Psalm 110 v. 1: “The Lord said to my Lord.”)

Where the Hebrew text reads Lord, YHWH, rather than the obvious tautology Lord,

LORD, most versions read Lord God (with or without capitalization). In such

cases, the word God becomes a substitute word in translation for the TG.

To try and make a distinction in Exodus 6:3 some RC versions have

transliterated the Hebrew word for Lord as ADONAI – cf. Douay-Challoner and

Knox (1955*).

JEHOVAH

The three vowel sounds in the pointing used by the Massoretes led

eventually to the sound Jehovah in Latin and then English. The first to use

this form in English translation (as Iehouah) was William Tyndale (1530*). Some

writers still erroneously credit him with inventing this spelling.7 Tyndale used Iehouah at Exodus 6 v. 3 and LORD elsewhere. The earliest

English version to regularly use Jehovah where the TG occurs appears to be that

of Henry Ainsworth (1622*). This writer has the 1639 folio of Ainsworth’s

Annotations upon the five books of Moses and the books of Psalms, printed by M.

Parsons for John Bellamie, and Jehovah (or Iehovah) is used throughout.

According to Herbert, Ainsworth’s Psalms first appeared in 1612, and the

Pentateuch from 1616. In his annotation on Genesis 2 v. 4, Ainsworth commented:

“Iehovah - this is Gods proper name.

It commeth of Havah, he was, and by the firft letter I. it fignifieth,

he will be, and by the fecond Ho, it fignifieth, he is…Paft, prefent and to

come are comprehended in this proper name as is knowne unto all…It implieth

alfo, that God hath his being or exiftence of himselfe before the world was,

that he giveth being unto all things…that he giveth being to his word effecting

whatfoever he fpeaketh.” (Although outside the scope of this article it should

be noted that the form Jehova was previously used extensively in the Latin

Bible of Tremellio and Junio first published in four parts over 1575-79.)

A little later in the 17th century than Ainsworth, the poet John Milton

published his translation of the first eight Psalms (c. 1653 and now sometimes

found bound with his poetry) in which he uses Jehovah fourteen times.

The 18th century saw a number of portion translations use Jehovah

extensively, such as Lowth’s Isaiah (1778*), Newcome’s Minor Prophets (1785*).

Dodson’s Isaiah (1790) and Street’s Psalms (1790*). The 19th century brought a

flood of new translations that consistently used this form for the TG,

including those by Benjamin Boothroyd (from 1824*). George R. Noyes (from

1827*), Charles Wellbeloved et al. (from 1859*). Robert Young (1862*), Samuel

Sharpe (1865*). Helen Spurrell (1885*) and John Nelson Darby (1885*). The 20th

century has seen other forms of the TG gain in popularity, but Jehovah has

still been the consistent choice of the American Standard Version (I901*), the

RC Westminster Version (from 1934*), New World Translation of the Hebrew

Scriptures (from 1953*), Steven T. Byington’s Bible in Living English (1972),

Jay Green’s Hebrew-English Interlinear (1976) and less consistently in Kenneth

Taylor’s Living Bible (1971). The popular New English Bible (1961*) uses

Jehovah in such verses as Exodus 6 v. 3.

A large number of portion translations and lesser known works could be

added to this list. However unusual the sound might appear to an ancient

Hebrew, after centuries of use “Jehovah seems firmly rooted in the English

language.”8

YAHWEH

Based partly on studies of proper names that incorporate the TG, many scholars

favor Yahweh as the correct pronunciation. The use of this Hebrew form has

steadily increased in recent years.

Who then was first to use Yahweh in translation? It is not so easy to be

categorical. Certainly the first major translation of the complete OT to

consistently feature Yahweh was J. B. Rotherham’s Emphasized Bible. The OT was

first published in 1902*. Rotherham devotes much space to explain his use of

Yahweh in preference to the popular form Jehovah. 9 Interestingly, in his later Studies in the Psalms (1911) Rotherham

reverted to Jehovah on the grounds of easy recognition.10

However, Rotherham was not the first in print with Yahweh. Just one year

earlier in 1901* James McSwiney’s translation of the Psalms and Canticles used

the form YaHWeh on occasion. If McSwiney should prove to be first this is

perhaps a little unfair on Rotherham. His OT translation was already completed

by 1894, when the publication of Ginsburg’s Critico-Massoretic Hebrew Text

caused him to delay publication to revise the whole work. 11

Since the turn of the century many others have followed these examples.

The Colloquial Speech Version (from 1920*) published by the National Adult

School Union used Yahweh. So did many translations of portions, such as S. R.

Driver’s Jeremiah (1906), Gowen’s Psalms (1930), Oesterley’s Psalms (1939) and

Watt’s Genesis (1963). The 1960s saw a number consistently use this form

including the Anchor Bible (from 1964) and the popular Jerusalem Bible (1966).

A. B. Traina’s Holy Name Bible (1963) uses Yahweh, and is also

consistent in Hebrewizing other names as well. In Traina’s NT (1950*) Jesus is

Yahshua. 1979 saw the commencement of Kohlenberger’s NIV Hebrew Interlinear

using Yahweh. Additionally, many popular versions that use LORD have chosen

Yahweh for Exodus 6 v. 3, including An American Translation (1927*) and the

Basic English Bible (1949*).

Returning to the question of who was first to use this form - if one

allows for variant spelling, one can go back at least to 1881* when J. M.

Rodwell’s Isaiah used the form Jahveh. The same spelling was used in T. H.

Wilkinson’s Job (1901*) and G. H. Box’s Isaiah (1908*). Other spellings since

then include Jahweh used by Edward J. Kissane in Job (1939*) and Isaiah (two

volumes: 1941-43*). In his Psalms (two volumes: 1953~54*) Kissane reverted to

the traditional spelling: Yahweh. Another slight variant is Iahweh used in

Bernard Duhm’s translation of The Twelve Prophets (1912). Yet another is Jave

used on a number of occasions by Ronald Knox in his OT (two volumes: 19490)12 In the popular one volume Bible of 1955 Knox dropped this completely

and reverted to LORD in the text and Yahweh in occasional footnotes. Then there

is Yahvah used in the Restoration of Original Sacred Name Bible (1976), a

revision of Rotherham’s translation. Like the similar work of Traina this also

Hebrewizes other names. In the NT (1968) Jesus becomes Yahvahshua.

TETRAGRAMMATON

Another approach has been to literally include the TG as four letters in

the translation. “In the Beginning - A New Translatin of Genesis” by Everett

Fox, consistently uses YHWH in the main text. Of course this is

unpronounceable! In his forward (p. xxix) Fox discusses the use of Lord,

Jehovah and Yahweh, and advises “as one reads the translation aloud one should

pronounce the name according to ones custom.” Here we have a modern translator

truly being “all things to all men” (1 Cor. 9 v. 22 NIV).

This device had previously been used by several late 19th century

versions. J. Helmuth’s literal translation of Genesis (1884) and E. G. King’s

Psalms (1898) both favored the form YHVH. Another slight variation was provided

by the Polychrome Bible (c. 1890s) which used JHVH. Additionally, a number of

Jewish versions use the TG in Hebrew characters at Exodus 6:3 with a footnote advising

the reader to substitute “Lord” – cf. New Jewish Bible (from 1962) and JPS ed.

Margolis (1917*).

While these forms are unpronounceable, they can at least be recognized

by the average student. But what does one make of the Concordant Version OT (Genesis

1958*) that consistently uses Ieue? On close examination of the CV’s

transliteration key Ieue proves to be none other than YHWH. The pronunciation

guide suggests it should be read as Yehweh - which at least looks more

familiar! After publishing all the prophets using Ieue, the translators with

Leviticus (1983) reverted to the form Yahweh.

ETERNAL

Jehovah, Yahweh and similar forms are often described as

transliterations since they incorporate in some way the four letters YHWH

(JHVH). In this area of semantics, Eternal is a rare attempt at actual

translation; in other words, an attempt to express the meaning of the name! 13 Most authorities link the TG with the Hebrew verb “to be” (or “to

become”) and it has been variously defined as “the one who is, who was and who

will be,”14 “to exist - to be actively present”15 and “he causes to be.”16 (cf. Henry Ainsworth

quotation above).

As translation “The Eternal” has been criticized 17 and apart from James Moffatt (1924*) few others in English have used

it, although it is popular in French translations like Segond. In his forward

Moffatt explains how he was poised to use Yahweh, and had he been translating

for students of the original would have done so, but almost at the last moment

followed the practice of the French scholars.18 Isaac Leeser (1854*) had previously used Eternal in Exodus 6 v. 3,

Psalm 83 v. 18, and in an unusual combination for a Jewish version at Isaiah 12

v. 2 as “Yah the Eternal.”

Even if it could be agreed that Eternal (or another expression)

accurately conveys the meaning, all other names in translation remain as names.

Why should different rules apply here? One awaits with some trepidation an

English version that translates the meaning of all names. The appearance of a

“Sacred Meaning Scripture Names Version” can only be a matter of time.

This article has concentrated on the TG in the OT and the various

decisions translators have made. Over the years a few NT translations have

appeared that have also included the TG in some recognizable form. The basis

for this has usually been in OT quotations, and more recently on the evidence

of some early Septuagint fragments. This more controversial area can perhaps

form the basis of a future article.

Footnotes

1 - An American Translation, preface p. xiii.

2 - Exodus 6 v. 3, Psalm 83 v. 18, Isaiah 12 v. 2 and 26 v. 4 (also in a

few compound place names)

3 - Jay Green: Interlinear Hebrew/English Bible (1976) preface p. xi.

4 - J. B. Rotherham: Emphasized Bible (1902) Introduction p. 22.

5 - Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible

1525-1961, Darlow and Moule (revised A. S.

Herbert) BFBS 1968. A number of the portion translations mentioned in

this article are not in Herbert.

6 - Bible Translator, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Oct. 1985). pp. 413. 414.

7 – cf. Dennett: Graphic Guide to Modern Versions of the NT (1965) p.

24. The spelling Iohouah was used by

Porchetus de Salvaticus in 1303 (Victoria Porcheti adversus impios

Hebraeos).

8 - Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1 and 2 Samuel) 1930

edition. Note 1. On the Name Jehovah. p. 10.

9 - Rotherham: Forward. pp. 22-29.

10 - Studies in the Psalms (1911). Introduction, p. 29.

11 - Rotherham: Forward, p. 17.

12 - Knox (1949 two volume edition) Psalm 67 v. 5. 21; 73 v. 18: 82 v.

19; Isaiah 42 v. 8; 45 v. 5, 6; etc.

13 - Bible Translator, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Oct. 1985). pp. 401, 402.

14 - Idem. p. 402.

15 - Lion Handbook of the Bible (1973) p. 157.

16 - Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (1962) Vol. 2, p. 410.

17 - Steven T. Byington: Bible in Living English (1972). Preface p. 7:

“much worse by a substantivized adjective.”

See also Bible Translator Vol. 36, No. 2 (Oct. 1985), p. 411.

18 - James Moffatt: Forward pp. xx, xxi.

The promised article on New Testament translations using some form

of the Tetragrammaton was never completed, but some of the research ended up in

the book Your Word is Truth: Essays in Celebration of the 50th

Anniversary of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, edited by

Anthony Byatt and Hal Flemings (published 2004).

Saturday, 16 November 2019

Laura J Raynor

A sister in law of Charles Taze Russell

From Highwood Cemetery, Pittsburgh

Laura

Raynor, Maria Russell’s older sister, was a keen supporter of ZWT theology for

a number of years, although you wouldn’t know it from her obituary in the

Pittsburgh Press, 23 July 1917.

The

obituary mentions her siblings, Lemuel Ackley (whose murder is covered in the

article “Lemuel” earlier on this blog), Selena Barto (who featured indirectly

in Lemuel’s demise), and of course Maria and Emma who married the Russells, son

and father.

ZWT

mentions a “Sister Raynor” sharing in colporteur work in 1887. Laura had been

widowed some years before this in 1873. Her husband, Henry Raynor had been

under 40 years old at the time, leaving her with three children, Howard M

Raynor (c.1867-1946), Selina Raynor, who never married (c.1865-1948), and Maria

Raynor (c.1873-after 1941). Maria Raynor married S Frank McKee and she is named

as May Raynor McKee on his death certificate in 1941. The whole family and

offshoots stayed in the general Pittsburgh area.

At

the time she was mentioned as a colporteur in 1887, Laura’s children would have

been of an age to be mainly independent; Selina would have been around 21,

Howard around 20, and Maria (May) around 14. They were also all listed as

living in the same home as Laura’s mother, Selina Ackley, back in the 1880

census.

Laura

is mentioned several times in subsequent issues of ZWT. In the May 1, 1892

issue for example, there was a meeting at her home. In the 1894 troubles, she

signed a document with her sister Maria and others supporting CTR. However, in

the 1897 troubles between CTR and Maria, she supported Maria.

Tuesday, 12 November 2019

Contact Card

The above

contact card was for Mrs M A Boder. Mary Ann Dunbar (1860-1948) was from

Scots-Irish background and married William F Boder in Allegheny in 1889. They

had one son, William Dunbar Boder (1891-1980).

Mary is

mentioned once in ZWT in the issue for August 15, 1908. She signed a document giving support to “the

vow” as part of the Avalon class (Avalon, Allegheny, Penn.) The document was also signed by W D Boder.

This was not her husband but her son who would be about 17 years old at the

time.

Mary

remained with the IBSA and her funeral announcement in 1948 mentioned Jehovah’s

Witnesses. From the Pittsburgh-Sun Telegraph, March 7,1948, page 33.

I do not

know her son’s subsequent religious history other than that he claimed

exemption on his 1917 WW1 Draft card on the grounds of being a member of the

International Bible Students. From a document dated June 5, 1917.

Saturday, 9 November 2019

Colporteur's prospectus

A 1904 edition of Divine Plan of the Ages with the prospectus for all six volumes bound as the cover. Very shortly after this was produced the title of the series was changed to Studies in the Scriptures.

Friday, 8 November 2019

Age to Come Bibles

Any detailed history of Watch Tower antecedents must contain

references to the Age to Come movement. This was a very general movement

covering different viewpoints that grew in the 19th century. When

CTR and his family met in Quincy Hall, Allegheny, this was originlly a combined

group of both Second Adventists and Age to Come believers, and advertised in

their respective papers. In the 1870s this tended to fall apart, as separation

and denominationalism came into being. The article that follows was published

in the specialist magazine Bible Review Journal Volume 2 number 2 (Fall 2015).

A previously posted article on this blog on Herman Heinfetter was published in

an earlier journal of this group,The International Society of Bible Collectors.

Keen collectors of Bible translations will often group different

versions into “families”, both by style and any underlying theology.

Stylistically they can range from extremely wooden literal versions to free –

sometimes wildly free – paraphrases. Under theology you can find what might be

called Catholic Bibles, Jewish Bibles, Baptist/immersionist Bibles, Unitarian

Bibles – to name but a few. Most Bible students are happy to have a

representative selection of all types for comparison purposes, even if they

personally hold views that are not always supported as they would wish by all

the versions on offer.

This article is going to discuss what I have perhaps arbitrarily

called Age to Come Bibles. This general grouping came to prominence in the 19th

century, and is sometimes confused with the Adventist movement with whom some

fellowshipped for a time. Ultimately, other than a mutual interest in the

return of Christ – there were sufficient differences in belief to cause

separation as the 19th century wore on. This led to clearly defined

Adventist groups, and clearly defined Age to Come groups – the latter including

such names as Church of God, One Faith, Living Hope, Abrahamic Faith, and

Christadelphian.

As a rough and general description, Age to Come believers, are

non-Trinitarian, and generally Socinian in outlook (i.e. they do not believe

that Jesus’ literally existed before his human birth). They often disbelieve in

the concept of a personal devil. They believe that immortality is conditional

and future, dependant on resurrection. So immortal-soul and hell-fire

theologies are rejected. And they believe that man’s destiny is on the earth –

(what some would call heaven on earth) - and generally that prophecies about

Israel will literally be fulfilled with natural Israel.

Bibles produced from such a background may have subtle difference

when compared with, for instance, the King James Version. Understandably, the

theology of translators will reflect their beliefs – especially when there are

translation problems that might arguably be rendered in more than one way. As

such, some readers may be interested in examining them further.

To find what I have called Age to Come Bibles there are probably

two texts to check. The key one is Luke 23:43. In the King James or Authorized

Version it reads:

And Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, To

day shalt thou be with me in paradise.

This has been carried on in the majority of translations since

then. But the question is raised, did Jesus actually mean he and the criminal

would be in paradise such as heaven that same day, or was he speaking on that

day about some future time and place? Groups that believe in the inherent

immortality of the human soul would say that while Jesus body was in the grave,

his spirit/soul went straight to heaven. Groups that believe in conditional

immortality and soul-sleep (such as Age to Come believers) would argue that

this paradise promise related to the future, not that actual day. The

understanding of the passage will determine where the translator puts the

comma, since there are no commas in koine Greek.

The second text to check is probably the automatic one most

readers would go to – John 1:1. Since these groups are normally

non-Trinitarian, the King James Version’s rendering of the last clause as “and

the Word was God” can be problematic, unless the definition of “Word” still

allows for a non-Trinitarian approach.

There are three Bibles we are going to consider:

Benjamin Wilson’s Emphatic Diaglott (NT only)

Duncan Heaster’s New European Version (complete Bible)

Anthony Buzzard’s The One God, the Father, One Man Messiah

Translation (NT only)

The history of Wilson and his Diaglott is well documented, so

little needs repeating here. Benjamin Wilson and John Thomas (from whom came

the Christadelphians) were in fellowship in the mid-19th century,

but there came a parting of the ways. Subsequently, Wilson produced his

Diaglott. In 1902 the copyright came into the possession of Charles T Russell,

president of the Watch Tower Society. By the time the copyright lapsed, the

Watchtower Society’s policy was to make no charge for literature, so there was

no point in anyone else producing it until their stock was exhausted. Since then

a Church of God group with help from Christadelphians has produced an edition,

and being out of copyright there are several ways it can now be obtained.

The New European Version is a modern revision of the KJV and ASV

rather than a new translation from original languages. It is produced from

within the Christadelphian movement, and has an extensive commentary by Duncan

Heaster. The NT first came out in 2009 and the complete Bible in 2011. It is

published jointly by Carelinks Publishing and the Christadelphian Advancement

Trust.

Anthony Buzzard’s The One God, the Father, One Man Messiah

Translation is an original translation based on the United Bible Society’s

Standard Greek Text (edited by Bruce Metzger). It was published in 2014 by

Restoration Fellowship. It is a NT produced from within the Church of God

movement. Buzzard taught for decades at their Bible College. Part of the Church

of God’s history can be traced back to the ministry of Benjamin Wilson, who as

noted above had been a co-worker with John Thomas, before doctrinal differences

split them up.

So how do these three Bibles approach our two key texts?

First - Luke 23:43.

Each of them places the comma to support their belief that Jesus’

reference to “paradise” was in the future.

Benjamin Wilson: And said to him the Jesus: Indeed I say to thee

to-day, with me thou shalt be in the Paradise.

Duncan Heaster: And he said to him: Truly, I can

say to you today right now, that you will indeed be with me in paradise.

Anthony Buzzard: Jesus replied, “I promise you

today, you will indeed be with me in that future paradise.”

There is more divergence in the way they handle John 1:1.

Wilson’s

main text is similar to the KJV, reading: “the Logos was with GOD, and the Logos was God” – although a distinction

is made between GOD and God by the use of capitals. However, Wilson’s

interlinear rendering “and a god was the Word” provoked

controversy.

It has to be said that the translation “a god” goes back a long

way, at least to Edward Harwood’s Liberal Translation of 1768

("and was himself a divine person"). It was popularised by the

Unitarians who got hold of Archbishop Newcome’s New

Testament and “improved” it. Newcome’s Improved Version of 1808 reads

“and the word was a god” in the main text. This was picked up by the Abner

Kneeland translation (1822), and then Wilson in his

interlinear. Others like Herman Heinfetter (1851) in the UK did likewise.

However, whilst Wilson’s John 1:1 interlinear raised criticism

from mainstream Christendom, it did not sit all that well with some Age to Come

believers. If the Word is “a god” – and by that is suggested a literal person –

whose existence can be linked right back to “in the beginning” – that presents

a conflict with a Socinian belief that the literal person of the Christ only

came into existence with his human birth – having previously being an idea or

plan in the mind of God.

So our other two Age to Come Bibles handle John 1:1 quite

differently, because to them, the Word refers to Reason, or a Thought or Idea

in the mind of God.

First, Heaster’s reads:

In the

beginning was the word (logos), and the word was towards God, and the word was

Divine.

The translation “Divine” is quite a common rendering – found in

Moffatt, Smith-Goodspeed, Schonfeld and others. It basically takes the word

“theos” without the article and makes it an adjective, a descriptive word.

But then from verse 2 onwards in John’s gospel in the NEV, this

word (uncapitalised) is not “he” but “it”. But from verse 10 onwards including

verse 14 where “the word became flesh” the pronoun changes to “he” for the rest

of the chapter. Heaster makes it quite clear in his commentary that he views

the word as the inner thought, or plan or message of God.

Anthony Buzzard’s translation is even more obvious in the way it

understands John 1:1. It reads:

In the

beginning there was God’s grand design, and that declaration was with God,

related to Him as His project, and it was fully expressive of God himself.

Buzzard’s commentary identifies the word as the thinking or

concern or promise of God. And like Heaster he uses the neuter pronoun “it”

until verse 10 when the word becomes “he”.

There are other Bibles that could probably fit into this family,

but I have restricted myself to the Diaglott and its two obvious daughters,

both in presentation and in the history of their publishers. But in passing we

could mention the New World Translation of Jehovah’s Witnesses, which has some

similarities. For example, the comma in Luke is placed to show the paradise

promise as future, and “a god” is in the main text for John 1:1. However, unlike Wilson, the modern witnesses

believe in the pre-existence of Jesus, a personal Devil, and reject that

natural Israel still has a part to play in God’s plan.

Then there is the plethora of translations produced by strands of

the Sacred Name movement.

(Historically most Sacred Name groups can be traced

back to 20th century schisms in the 19th century Church

of God Seventh Day). Starting with Angelo B Traina’s Sacred Name Bible (1950

NT, whole Bible 1963), they include L D Snow’s and R Favitta’s Restoration of

Original Sacred Name Bible (1970) and Jacob Meyer’s Sacred Scriptures Bethel

Edition (1981) and Yisrayl Hawkins’

The Book of Yahweh (1988). These have been joined by some internet-only

versions in more recent years. These Sacred Name Bibles have doctrinal

similarities with Wilson et al. as reflected in our two key texts, Luke 23:43 and John 1:1, but add their own

distinctive take on Divine Names and titles. Some would

argue that “translation” is a misnomer for more recent examples, “adaptation”

being more accurate. The ability to get hold of an existing but out of

copyright Bible translation in electronic form and simply substitute their

“corrections” means that any Sacred Name group (however small) can still retain

its individuality by producing its own Bible. But these are outside the scope

of this article.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)