William Tyndale’s translation from Exodus 6 as first

published in 1530.

This blog has already

republished two articles from the journals of The International Society of

Bible Collectors, one on Herman Heinfetter and one on Age to Come Bibles. This

third article, which dates from 1988, was published originally in Bible

Collectors’ World. It has not been updated since its original publication.

The article was specific

to translations of the commonly called Old Testament. It has no direct

connection with the Bible Student movement (although ZWT used the name Jehovah

over two thousand two hundred times, starting with the supplement to the very

first issue of July 1879 through to the end of 1916). And the modern Watchtower

Society has produced the New World Translation, which extensively uses the form

Jehovah. As such, the subject matter may be of interest to some blog readers.

Footnote numbers are

printed in red.

A past issue of The Bible Collector (No. 57) contained an article on

“The Divine Name in Bible Translation.” This described some Bible versions of

the past 150 years that restored the Divine Name in the text in some readable

form, generally as Jehovah or Yahweh. The purpose of this article is to

illustrate how this translation problem has been handled in at least a dozen

different ways in English language versions of the Old Testament (OT).

The background only need be covered briefly here. The special name for

God in the Hebrew text is written as four letters (Greek: tetragrammaton,

hereinafter abbreviated at TG). These letters are usually transliterated as

YHWH. By about 700 AD Jewish “masters of tradition” (Massoretes) were adding a

system of vowel points to indicate the accepted pronunciation. When handling

the TG, vowel points for Adonai (Lord) and Elohim (God) were deliberately

inserted. This reminded the reader that “Lord” or “God” should be substituted

in public reading. It had long been Jewish practice not to pronounce the sacred

name. When translations were made into Greek, and later Latin, it became

accepted practice to substitute words such as “Lord” in the translation. The

first English versions from the Latin simply passed on this earlier decision.

This background has resulted in two opposing viewpoints amongst

translators today. One is to follow the long established practice of

substituting a title for the TG, usually LORD in all capitals. Smith and Goodspeed’s

American Translation calls this following “the orthodox Jewish tradition.” 1 However, there are certain texts such as Exodus 6:3 where many feel the

sense is incomplete without a proper name. On such occasions many leave

tradition and insert a form of the TG. This pattern, started with Tyndale, was

popularized by the KJV which used the form Jehovah on four occasions. 2

The alternative view is that the name should be consistently restored in

the English version, wherever this can be supported by the Hebrew text.

Depending on the actual text used this can vary between 5,500 3 and nearly 7,000 4 times. It is held

that later Jewish tradition should not be the determining factor. If the

earliest extant manuscripts (including the Dead Sea Scrolls) use a distinctive

name so many times, then accurate translation demands the same. But what form

should the name take?

There are of course many translations that do not fit comfortably into

either above category. Some appear very inconsistent, using names or titles on

the apparent whim of the translator (cf. Living Bible). The New Berkeley

Version (1969) even manages to contain both Jehovah (Exodus 6:3) and Yahweh

(Hosea 12:5) within the same translation!

An attempt will now be made to describe some different ways the TG has

been handled in the history of OT translation. The following survey does not

claim to be exhaustive. The dates in brackets relate to OT publication, which

in many cases will mean the complete Bible. An asterisk (*) following the date indicates

that the volume is featured in Herbert. 5

LORD/GOD

The reasons for substituting the title LORD have been outlined above.

Versions consistent in this practice include Revised Standard Version (1952*),

New American Bible (1970), New American Standard Version (1971), Good News

Bible (1976) and New International Version (1978). These are amongst the most

popular versions in use. The general reading public for whom they are addressed

can easily remain unaware of the TG, unless they check a forward or footnote.

Even in Exodus 6:3 the form LORD is retained.

It is interesting to note that the supervising translator of the Good

News Bible, Robert Bratcher, has recently commented: “A faithful application of

dynamic equivalence principles would require a proper name, and not a title, as

a translation of YHWH…In the matter of the names for God, the GNB is still far

from being a ‘perfect’ translation.” 6 It can also be noted that the NIV text used in Kohlenberger’s Hebrew

Interlinear (1979-86) has restored the form Yahweh.

Other popular versions of the 20th century that generally use LORD, but

make an exception in Exodus 6:3 include New English Bible (1961*). American

Translation (OT 1927*), and Basic English (1949*). The usual practice is to

print LORD in capitals when it substitutes for the TG. (This is not always the

case. The much reprinted Douay-Challoner version uses small case letters,

creating a problem of identity in Psalm 110 v. 1: “The Lord said to my Lord.”)

Where the Hebrew text reads Lord, YHWH, rather than the obvious tautology Lord,

LORD, most versions read Lord God (with or without capitalization). In such

cases, the word God becomes a substitute word in translation for the TG.

To try and make a distinction in Exodus 6:3 some RC versions have

transliterated the Hebrew word for Lord as ADONAI – cf. Douay-Challoner and

Knox (1955*).

JEHOVAH

The three vowel sounds in the pointing used by the Massoretes led

eventually to the sound Jehovah in Latin and then English. The first to use

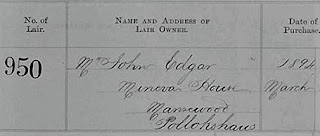

this form in English translation (as Iehouah) was William Tyndale (1530*). Some

writers still erroneously credit him with inventing this spelling.7 Tyndale used Iehouah at Exodus 6 v. 3 and LORD elsewhere. The earliest

English version to regularly use Jehovah where the TG occurs appears to be that

of Henry Ainsworth (1622*). This writer has the 1639 folio of Ainsworth’s

Annotations upon the five books of Moses and the books of Psalms, printed by M.

Parsons for John Bellamie, and Jehovah (or Iehovah) is used throughout.

According to Herbert, Ainsworth’s Psalms first appeared in 1612, and the

Pentateuch from 1616. In his annotation on Genesis 2 v. 4, Ainsworth commented:

“Iehovah - this is Gods proper name.

It commeth of Havah, he was, and by the firft letter I. it fignifieth,

he will be, and by the fecond Ho, it fignifieth, he is…Paft, prefent and to

come are comprehended in this proper name as is knowne unto all…It implieth

alfo, that God hath his being or exiftence of himselfe before the world was,

that he giveth being unto all things…that he giveth being to his word effecting

whatfoever he fpeaketh.” (Although outside the scope of this article it should

be noted that the form Jehova was previously used extensively in the Latin

Bible of Tremellio and Junio first published in four parts over 1575-79.)

A little later in the 17th century than Ainsworth, the poet John Milton

published his translation of the first eight Psalms (c. 1653 and now sometimes

found bound with his poetry) in which he uses Jehovah fourteen times.

The 18th century saw a number of portion translations use Jehovah

extensively, such as Lowth’s Isaiah (1778*), Newcome’s Minor Prophets (1785*).

Dodson’s Isaiah (1790) and Street’s Psalms (1790*). The 19th century brought a

flood of new translations that consistently used this form for the TG,

including those by Benjamin Boothroyd (from 1824*). George R. Noyes (from

1827*), Charles Wellbeloved et al. (from 1859*). Robert Young (1862*), Samuel

Sharpe (1865*). Helen Spurrell (1885*) and John Nelson Darby (1885*). The 20th

century has seen other forms of the TG gain in popularity, but Jehovah has

still been the consistent choice of the American Standard Version (I901*), the

RC Westminster Version (from 1934*), New World Translation of the Hebrew

Scriptures (from 1953*), Steven T. Byington’s Bible in Living English (1972),

Jay Green’s Hebrew-English Interlinear (1976) and less consistently in Kenneth

Taylor’s Living Bible (1971). The popular New English Bible (1961*) uses

Jehovah in such verses as Exodus 6 v. 3.

A large number of portion translations and lesser known works could be

added to this list. However unusual the sound might appear to an ancient

Hebrew, after centuries of use “Jehovah seems firmly rooted in the English

language.”8

YAHWEH

Based partly on studies of proper names that incorporate the TG, many scholars

favor Yahweh as the correct pronunciation. The use of this Hebrew form has

steadily increased in recent years.

Who then was first to use Yahweh in translation? It is not so easy to be

categorical. Certainly the first major translation of the complete OT to

consistently feature Yahweh was J. B. Rotherham’s Emphasized Bible. The OT was

first published in 1902*. Rotherham devotes much space to explain his use of

Yahweh in preference to the popular form Jehovah. 9 Interestingly, in his later Studies in the Psalms (1911) Rotherham

reverted to Jehovah on the grounds of easy recognition.10

However, Rotherham was not the first in print with Yahweh. Just one year

earlier in 1901* James McSwiney’s translation of the Psalms and Canticles used

the form YaHWeh on occasion. If McSwiney should prove to be first this is

perhaps a little unfair on Rotherham. His OT translation was already completed

by 1894, when the publication of Ginsburg’s Critico-Massoretic Hebrew Text

caused him to delay publication to revise the whole work. 11

Since the turn of the century many others have followed these examples.

The Colloquial Speech Version (from 1920*) published by the National Adult

School Union used Yahweh. So did many translations of portions, such as S. R.

Driver’s Jeremiah (1906), Gowen’s Psalms (1930), Oesterley’s Psalms (1939) and

Watt’s Genesis (1963). The 1960s saw a number consistently use this form

including the Anchor Bible (from 1964) and the popular Jerusalem Bible (1966).

A. B. Traina’s Holy Name Bible (1963) uses Yahweh, and is also

consistent in Hebrewizing other names as well. In Traina’s NT (1950*) Jesus is

Yahshua. 1979 saw the commencement of Kohlenberger’s NIV Hebrew Interlinear

using Yahweh. Additionally, many popular versions that use LORD have chosen

Yahweh for Exodus 6 v. 3, including An American Translation (1927*) and the

Basic English Bible (1949*).

Returning to the question of who was first to use this form - if one

allows for variant spelling, one can go back at least to 1881* when J. M.

Rodwell’s Isaiah used the form Jahveh. The same spelling was used in T. H.

Wilkinson’s Job (1901*) and G. H. Box’s Isaiah (1908*). Other spellings since

then include Jahweh used by Edward J. Kissane in Job (1939*) and Isaiah (two

volumes: 1941-43*). In his Psalms (two volumes: 1953~54*) Kissane reverted to

the traditional spelling: Yahweh. Another slight variant is Iahweh used in

Bernard Duhm’s translation of The Twelve Prophets (1912). Yet another is Jave

used on a number of occasions by Ronald Knox in his OT (two volumes: 19490)12 In the popular one volume Bible of 1955 Knox dropped this completely

and reverted to LORD in the text and Yahweh in occasional footnotes. Then there

is Yahvah used in the Restoration of Original Sacred Name Bible (1976), a

revision of Rotherham’s translation. Like the similar work of Traina this also

Hebrewizes other names. In the NT (1968) Jesus becomes Yahvahshua.

TETRAGRAMMATON

Another approach has been to literally include the TG as four letters in

the translation. “In the Beginning - A New Translatin of Genesis” by Everett

Fox, consistently uses YHWH in the main text. Of course this is

unpronounceable! In his forward (p. xxix) Fox discusses the use of Lord,

Jehovah and Yahweh, and advises “as one reads the translation aloud one should

pronounce the name according to ones custom.” Here we have a modern translator

truly being “all things to all men” (1 Cor. 9 v. 22 NIV).

This device had previously been used by several late 19th century

versions. J. Helmuth’s literal translation of Genesis (1884) and E. G. King’s

Psalms (1898) both favored the form YHVH. Another slight variation was provided

by the Polychrome Bible (c. 1890s) which used JHVH. Additionally, a number of

Jewish versions use the TG in Hebrew characters at Exodus 6:3 with a footnote advising

the reader to substitute “Lord” – cf. New Jewish Bible (from 1962) and JPS ed.

Margolis (1917*).

While these forms are unpronounceable, they can at least be recognized

by the average student. But what does one make of the Concordant Version OT (Genesis

1958*) that consistently uses Ieue? On close examination of the CV’s

transliteration key Ieue proves to be none other than YHWH. The pronunciation

guide suggests it should be read as Yehweh - which at least looks more

familiar! After publishing all the prophets using Ieue, the translators with

Leviticus (1983) reverted to the form Yahweh.

ETERNAL

Jehovah, Yahweh and similar forms are often described as

transliterations since they incorporate in some way the four letters YHWH

(JHVH). In this area of semantics, Eternal is a rare attempt at actual

translation; in other words, an attempt to express the meaning of the name! 13 Most authorities link the TG with the Hebrew verb “to be” (or “to

become”) and it has been variously defined as “the one who is, who was and who

will be,”14 “to exist - to be actively present”15 and “he causes to be.”16 (cf. Henry Ainsworth

quotation above).

As translation “The Eternal” has been criticized 17 and apart from James Moffatt (1924*) few others in English have used

it, although it is popular in French translations like Segond. In his forward

Moffatt explains how he was poised to use Yahweh, and had he been translating

for students of the original would have done so, but almost at the last moment

followed the practice of the French scholars.18 Isaac Leeser (1854*) had previously used Eternal in Exodus 6 v. 3,

Psalm 83 v. 18, and in an unusual combination for a Jewish version at Isaiah 12

v. 2 as “Yah the Eternal.”

Even if it could be agreed that Eternal (or another expression)

accurately conveys the meaning, all other names in translation remain as names.

Why should different rules apply here? One awaits with some trepidation an

English version that translates the meaning of all names. The appearance of a

“Sacred Meaning Scripture Names Version” can only be a matter of time.

This article has concentrated on the TG in the OT and the various

decisions translators have made. Over the years a few NT translations have

appeared that have also included the TG in some recognizable form. The basis

for this has usually been in OT quotations, and more recently on the evidence

of some early Septuagint fragments. This more controversial area can perhaps

form the basis of a future article.

Footnotes

1 - An American Translation, preface p. xiii.

2 - Exodus 6 v. 3, Psalm 83 v. 18, Isaiah 12 v. 2 and 26 v. 4 (also in a

few compound place names)

3 - Jay Green: Interlinear Hebrew/English Bible (1976) preface p. xi.

4 - J. B. Rotherham: Emphasized Bible (1902) Introduction p. 22.

5 - Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible

1525-1961, Darlow and Moule (revised A. S.

Herbert) BFBS 1968. A number of the portion translations mentioned in

this article are not in Herbert.

6 - Bible Translator, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Oct. 1985). pp. 413. 414.

7 – cf. Dennett: Graphic Guide to Modern Versions of the NT (1965) p.

24. The spelling Iohouah was used by

Porchetus de Salvaticus in 1303 (Victoria Porcheti adversus impios

Hebraeos).

8 - Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1 and 2 Samuel) 1930

edition. Note 1. On the Name Jehovah. p. 10.

9 - Rotherham: Forward. pp. 22-29.

10 - Studies in the Psalms (1911). Introduction, p. 29.

11 - Rotherham: Forward, p. 17.

12 - Knox (1949 two volume edition) Psalm 67 v. 5. 21; 73 v. 18: 82 v.

19; Isaiah 42 v. 8; 45 v. 5, 6; etc.

13 - Bible Translator, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Oct. 1985). pp. 401, 402.

14 - Idem. p. 402.

15 - Lion Handbook of the Bible (1973) p. 157.

16 - Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (1962) Vol. 2, p. 410.

17 - Steven T. Byington: Bible in Living English (1972). Preface p. 7:

“much worse by a substantivized adjective.”

See also Bible Translator Vol. 36, No. 2 (Oct. 1985), p. 411.

18 - James Moffatt: Forward pp. xx, xxi.

The promised article on New Testament translations using some form

of the Tetragrammaton was never completed, but some of the research ended up in

the book Your Word is Truth: Essays in Celebration of the 50th

Anniversary of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, edited by

Anthony Byatt and Hal Flemings (published 2004).